Reverse engineered parts are components recreated by capturing the geometry, material intent, and functional requirements of an existing item – often when drawings are missing, suppliers have vanished, or equipment has been modified over time. Done well, reverse engineering is not “copying a shape”; it’s a controlled engineering process that turns a physical part into reliable manufacturing data (CAD, drawings, inspection criteria) so you can make accurate replacements, introduce improvements, or keep critical assets running.

This guide explains how reverse engineered parts are produced, where the risks are, how to specify what you actually need, and how to avoid common pitfalls, without the fluff.

What Are Reverse Engineered Parts?

Reverse engineered parts are manufactured using information derived from an existing component rather than the original design package. The starting point might be a worn sample, a broken assembly, a cast item with no drawings, or a 3D scan of an installed component that cannot be removed for long. The goal is to create a usable definition of the part – geometry, tolerances, materials, finishes, and functional interfaces – so it can be produced again consistently.

When people talk about reverse engineered parts, they usually mean one (or more) of the following outcomes:

- A 3D CAD model of the part (solid or surface)

- 2D engineering drawings with tolerances and notes

- A “manufacturing pack” (CAD + drawing + inspection plan)

- A batch of replacement parts made to an agreed specification

- A redesigned “functionally equivalent” part that improves performance or manufacturability

Why Reverse Engineered Replacement Parts Are In Demand

Reverse engineered replacement parts are common in sectors where uptime matters and product lifecycles are long: industrial machinery, aerospace support equipment, medical devices (non-patient-contact tooling), automation, packaging, energy, marine, rail, and specialist vehicles. Many organisations discover they’re one obsolete part away from a prolonged shutdown.

Typical drivers include:

- Obsolescence: the OEM no longer supports the part or has discontinued it

- Missing data: drawings and CAD are lost, incomplete, or never existed

- Supplier risk: single-source parts with long lead times or poor availability

- Modifications: equipment has been altered so the original drawing no longer matches reality

- Performance issues: the “same” part keeps failing and needs improvement

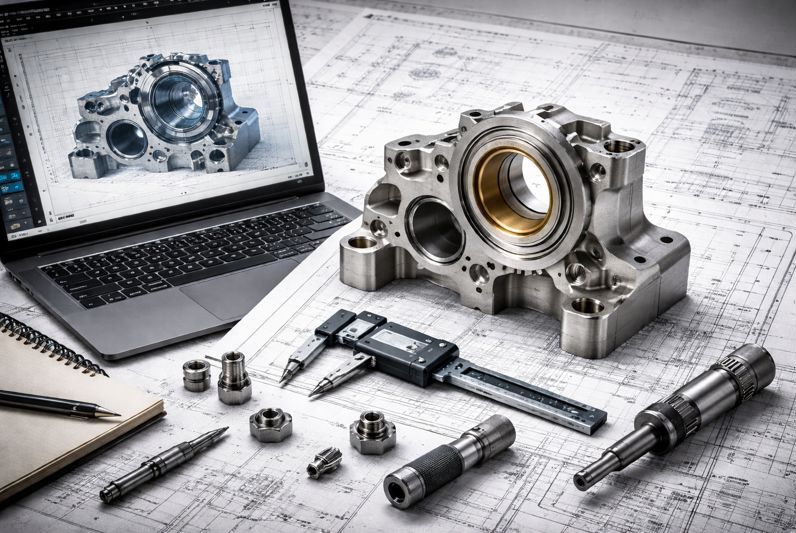

The Reverse Engineering Process for Parts

A robust reverse engineering process for parts moves from “what we can measure” to “what we should manufacture.” That means capturing geometry accurately, understanding function, and deciding what tolerances matter. The best projects start by agreeing the intent: do you need an identical replica, or a part that fits and functions (even if the geometry changes)?

A typical workflow looks like this:

- Requirement definition: fit/function, critical interfaces, operating environment, acceptable substitutions

- Data capture: 3D scanning, CMM measurement, hand metrology, photographs, and notes

- CAD reconstruction: turning raw measurement data into a manufacturable model

- Design intent + tolerancing: adding datums, GD&T (where appropriate), and realistic tolerances

- Material and finish selection: matching performance, not just appearance

- Prototype and validation: first-off inspection, assembly checks, functional test if needed

- Production release: controlled drawings, revision history, and an inspection plan

3D Scanning for Reverse Engineered Parts

3D scanning is often the fastest way to capture complex geometry, especially organic shapes, castings, worn contours, and assemblies with tricky access. But scan data alone is not a manufacturing definition. Most scans produce a “point cloud” or mesh that needs interpretation to create CAD model surfaces and precise features (holes, planes, threads, datums). If you’re considering 3D scanning for reverse engineered parts, it helps to understand what scanning is good at and where it needs support:

- Great for: freeform surfaces, cast shapes, ergonomics, housings, ducting, legacy moulded parts

- Less direct for: true position of holes, threads, sharp edges, critical planes (often better via CMM)

- Common need: hybrid approach – scan for form + CMM for precise features

Metrology and Measurement for Reverse Engineered Components

Measurement is the backbone of reliable reverse engineered components. The main challenge is separating “as-manufactured intent” from “as-worn reality.” A part that has run for 10 years may be distorted, polished, fretted, or plastically deformed – so copying it perfectly can reproduce the wear, not the design.

A good measurement plan typically includes:

- Data strategy: deciding what features define the part’s coordinate system

- Critical feature identification: interfaces, sealing faces, bearing seats, hole patterns, alignment features

- Environmental control: temperature stability, cleanliness, and measurement uncertainty

- Multiple samples (if possible): comparing two or three parts to infer original intent

Creating CAD Models for Reverse Engineered Parts

Turning measurements into CAD models for reverse engineered parts is where engineering judgement matters most. You’re not just tracing a mesh, you’re rebuilding geometry so it’s editable, dimensionable, and manufacturable. That usually means recognising cylinders, cones, planes, fillets, and true feature relationships, then deciding what should be nominal.

Common CAD deliverables include:

- Solid model: ideal for CNC machining, inspection programming, and revisions

- Surface model: useful for freeform geometry where solid reconstruction is heavy

- Parametric features: hole callouts, patterns, pockets, boss features, threads

- Drawing pack: dimensions, datums, GD&T (if used), material, finish, and notes

Materials and Finishes When Replicating Reverse Engineered Parts

Material selection for reverse engineered parts should be performance-led. If the original spec is unknown, you can often infer material family from application, magnetism, density, hardness, corrosion pattern, or machining characteristics. For critical components, lab testing can remove guesswork. After you’ve defined the operating environment (temperature, chemicals, load cycles, lubrication, galvanic couples), you can make sensible choices such as:

- Metals: aluminium alloys, stainless steels, tool steels, nickel alloys, bronze/brass

- Plastics: acetal, nylon, UHMW-PE, PTFE, PEEK, PPS, PVDF (depending on use)

- Finishes/coatings: anodising, passivation, plating, nitriding, paint, hard coatings

Where parts interact (bearings, seals, sliding surfaces), surface finish and hardness can matter as much as material grade.

Tolerances and GD&T for Reverse Engineered Parts

A major mistake with reverse engineered parts is over-tolerancing. It’s tempting to apply tight tolerances “just to be safe,” but that can drive cost up fast – and sometimes makes parts harder to assemble if the original design allowed compliance or adjustment.

A better approach is to tolerance based on function:

- Interface-first tolerancing: tight where it locates, seals, or rotates; relaxed elsewhere

- Datum selection: choose datums that reflect how the part is used in assembly

- Process capability: match tolerances to the manufacturing method (CNC, grinding, EDM, moulding)

- Inspection strategy: ensure every critical tolerance is actually measurable

If you don’t have an assembly drawing, simple fit checks (with mating parts or gauges) can be more informative than chasing microns everywhere.

Handling Wear, Damage and “Unknown Intent” in Reverse Engineered Replacement Parts

Reverse engineered replacement parts often start with imperfect samples. When that happens, the job becomes part detective work: what dimensions are functional, what is wear, and what was never critical? Sometimes you can spot design intent in symmetry, patterns, standard fastener sizes, or common bearing/seal fits.

Practical ways to reduce risk include:

- Measure multiple areas: compare opposing faces and repeated features

- Use mating components: back-calculate hole positions and interface planes

- Reference standards: common thread series, dowel fits, bearing seat tolerances

- Decide on “functional equivalence”: replicate only what matters to performance

This is one area where an experienced manufacturing partner can help translate messy reality into a clean, controlled drawing. Tarvin Precision, for example, often sees legacy parts where the “real” work is agreeing datums and tolerances that make sense for repeatable CNC manufacture, not merely copying a worn sample.

Quality Control for Reverse Engineered Parts

Quality for reverse engineered parts should be defined upfront, not assumed. Without an original drawing, you need to agree how the part will be verified and what “pass” looks like. This usually involves a first article inspection approach and an inspection plan tied to the newly created drawing.

Common quality steps include:

- First-off inspection report: key dimensions, datums, and critical features

- CMM inspection: for hole patterns, true position, profiles, and flatness/parallelism

- Material verification: hardness testing, PMI (for alloys), or lab analysis if required

- Fit/function validation: assembly trial, leak test, rotation check, or load test (as applicable)

Even for one-off replacements, documenting what was measured and what was delivered pays off the next time the part is needed.

Legal and IP Considerations for Reverse Engineering Parts

Reverse engineered parts can be legitimate, but you should consider intellectual property and contractual restrictions. In many cases, creating a replacement for your own equipment is allowed, but copying proprietary designs for resale may raise patent, copyright, design rights, or trade secret issues depending on jurisdiction and specifics.

Before proceeding, it’s sensible to:

- Check ownership and contracts: maintenance agreements, licence terms, OEM restrictions

- Assess IP status: patents expire, but other protections may still apply

- Focus on functional need: “fit and function” replacements can reduce risk versus direct copying

- Document your process: keep records of measurements, requirements, and decisions

If the part is safety-critical, regulated, or tied to certified systems, you may also need compliance steps beyond standard manufacturing practice.

Applications: Where Reverse Engineered Components Add Real Value

Reverse engineered components can do more than keep old machines alive. They can also support upgrades, redesigns, and supply-chain resilience – especially when you treat the project as an engineering improvement, not a cloning exercise.

Common application areas include:

- Obsolete machine spares: brackets, guards, housings, mounts, gears, pulleys

- Production tooling: nests, fixtures, jigs, end-effectors, change parts

- Sealing and fluid components: manifolds, valve bodies, flanges, adaptors

- Precision interfaces: bearing carriers, alignment plates, sensor mounts

- Legacy plastics: covers, insulators, wear strips, sliders

Cost, Lead Time and How to Brief a Supplier

The cost of reverse engineered parts usually breaks down into two buckets: the one-time engineering work (capture + CAD + drawings) and the manufacturing work (machining/moulding + inspection). If you expect repeat demand, investing in a proper drawing pack often lowers total cost over time.

A strong brief reduces iterations. Provide what you can, even if it’s incomplete:

- What the part does: loads, motion, sealing, alignment, temperature/chemicals

- What “must match”: interfaces, hole patterns, thickness, mass constraints

- What can change: non-critical geometry, cosmetic surfaces, internal features

- How many you need now and later: one-off vs short run vs ongoing spares

- Any failure history: where it cracked, wore, loosened, or seized

Shops like Tarvin Precision will typically be discreet about the commercial context, but they can add value by suggesting manufacturable tolerances, sensible data schemes, and material alternatives when the original spec is unknown – without turning the conversation into a sales pitch.

Common Pitfalls with Reverse Engineered Parts

Reverse engineering can go sideways when assumptions aren’t made explicit. The good news is that most issues are preventable if you treat the project as controlled engineering, not “trace-and-cut.”

Watch out for these recurring problems:

- Copying wear: reproducing a distorted sample rather than restoring nominal intent

- No datum agreement: inconsistent measurement causes non-repeatable results

- Over-tolerancing: driving cost up without improving function

- Ignoring environment: wrong material/finish leads to corrosion, galling, swelling, or creep

- No validation plan: parts arrive “to CAD” but don’t assemble or perform

FAQ: Reverse Engineered Parts

Got a specific question about reverse engineered parts? These quick FAQs cover the most common practical details around measurement, CAD, materials, tolerances, and lead times.

Are reverse engineered parts as good as OEM parts?

They can be, sometimes better, if the process captures design intent and defines quality checks. If you only copy a worn sample without validation, results are less predictable.

Do I need 3D scanning for reverse engineered replacement parts?

Not always. Simple prismatic parts may be best measured with CMM and hand metrology. Complex castings, freeform surfaces, and ergonomics often benefit from scanning.

Can reverse engineered components be improved?

Yes. Many projects intentionally deliver a functionally equivalent part with better material, improved wear features, added radii, or geometry changes that reduce machining time, provided the interfaces remain correct.

How do I know what tolerances to use?

Start with function: locate, seal, rotate, align, or slide. Tolerance those features appropriately and keep everything else realistic. A supplier experienced in precision machining can help define tolerances that are measurable and cost-effective.

Getting Reverse Engineered Parts Right

Reverse engineered parts are most successful when you define the goal (replica vs fit-and-function), capture data with an appropriate measurement strategy, rebuild CAD with design intent, and validate the first-off part against how it will actually be used. If you do that, reverse engineered replacement parts become a dependable route to uptime, resilience, and sensible redesign – rather than an expensive guessing game.